Another week in the books, my friend. One of the things I'm wondering more and more about every day is what using generative AI will do to the next generation of my students. Yes, I'm on the train of people who love and embrace it, but I'm also using these AI tools with decades of writing experience. And I know that sometimes, I need to write without it and let my ideas flow to help me think. Because as I often said on social media, writing is thinking and helps me percolate ideas in my head. Sometimes that's needed and knowing when you need it, is becoming an increasingly unfair advantage for academics these days.

But I'm not one to dismiss AI tools right away and so we studied them in our research group and published a paper about our findings. And that's what I want to talk to you about today. The increasingly relevant question of whether or not we can spot AI writing. Here's the details.

Academic AI aversion: What it means for researchers

Remember when you were in high school and teachers would run your papers through some plagiarism detectors like TurnItIn with the steely glint of Sherlock Holmes, who just knew you copied that paragraph from Wikipedia? Well, academia has a new boogeyman, and its name is ChatGPT.

One of our recent studies shows something that should make us all reconsider our confidence in spotting AI-generated content: academic reviewers —you know, those gatekeepers of scholarly publishing with decades of specialized expertise (who go under the pseudonym of reviewer 2 in several memes)—are terrible at identifying AI-written research.

Like, truly awful at it. As in coin-flip levels of accuracy. Shocker.

Frustrated by academic bias against AI tools?

— Prof Lennart Nacke, PhD (@acagamic) November 5, 2024

If you’re using AI for writing, reviewers might be working against you.

But most reviewers can't tell if your research paper was written by AI.

(This changes how we think about academic writing)

Here's what my research team… pic.twitter.com/GpsDQpnO53

Our recent journal paper, The great AI witch hunt: Reviewers' perception and (Mis)conception of generative AI in research writing, published in the journal Computers in Human Behavior: Artificial Humans, goes full-on honey badger into this embarrassing reality. As someone who regularly uses AI writing tools in all of my writing (yes, I'm admitting to it publicly), this study was important to do. And my grad students, most of all first author Hilda Hadan, and postdocs did an amazing job with this early study on how AI shapes academia.

Time to bake why this matters into our brains. It's not just essential new evidence for researchers worried about being accused of cheating, but for all of us struggling to publish in a brave new world increasingly shaped by generative AI for everything we read (this article included).

Our experiment was a clever little AI trap

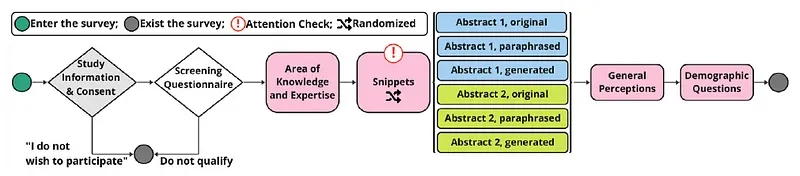

We set an elegant trap. We recruited 17 experienced peer reviewers from top human-computer interaction (HCI) conferences (like CHI) and presented them with research snippets in three flavours:

- Original: Written entirely by human researchers

- Paraphrased: Human text rewritten by AI (Google Gemini)

- Generated: Created entirely by AI based on human reference text

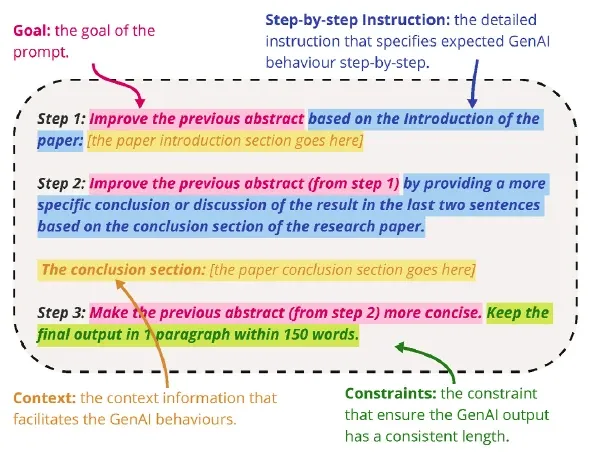

We detail the exact prompts we used for Gemini in our paper, but here is a taster of the prompt we used to generate a snippet:

Each reviewer read multiple snippets and had to judge: Was this written by a human or AI? They also rated the snippets on perceived honesty, clarity, accuracy, and other qualities.

The results? The academic reviewers were essentially guessing. They couldn't reliably tell the difference between AI-generated text and human writing. Bet you didn't see that one coming from a mile away.

Specifically, our reviewers:

- Rated original human-written snippets and AI-generated snippets as equally likely to involve AI (median score of 5 out of 10 for both!)

- Curiously, rated AI-paraphrased snippets as less likely to be AI-generated (median score of 2)

- Showed no significant difference in how they judged the quality of research across the three content types

Let that sink in. The very people who we might expect to be most sensitive to AI intrusion into their domain couldn't tell when AI was doing the writing - and when they thought they could tell, they were often wrong. Talk about generative AI going full Solid Snake on research fields. 🙃

Like finding a unicorn in your cereal bowl

Here’s where it gets even more interesting, I think. Unlike previous studies showing “algorithm aversion” (where people distrust AI outputs even when they’re objectively better), our sample of academic reviewers showed neither aversion nor appreciation.

Their judgments of research quality remained consistent regardless of perceived AI involvement. In other words, they weren’t downgrading papers just because they thought they detected AI’s fingerprints. Let that little nugget of insight find a cozy spot in your brain.

“I do think it was written by a human with good language skills,” commented Reviewer 14 about a snippet that was actually AI-paraphrased. How about that?

We found that reviewers who had greater expertise in the relevant field and more familiarity with AI tools consistently rated snippets higher on honesty, clarity, and persuasiveness. And this was regardless of whether humans or AI wrote them. This suggests that rather than being blinded by bias, these reviewers focused on the substance of the research. That’s like discovering your toast landed butter-side up. I certainly was surprised.

Contradictory clues

What made reviewers suspect AI involvement? Their responses were fascinatingly contradictory:

For sentence structure

- 27% said AI produces incoherent logic and phrasing

- But 7% said AI structures sentences better than humans

For sentence length

- 13% claimed AI tends to write convoluted, long sentences

- But 3% attributed convoluted, long sentences to human writers

For language use

- 21% said AI uses unusual language choices

- 10% associated plain, natural language with human authors

- But some claimed the exact opposite patterns

In essence, reviewers were using completely contradictory criteria to flag “AI writing,” revealing their inability to distinguish it systematically. You might as well play darts blindfolded.

One reviewer confidently declared: “AI tends to construct sentences that often have a ‘do-ing’ in the second half.” Another was sure that “The sentences are too well-structured to be human-written.” And while I agree with some of those notions, they are not perfect determinants. I feel we’re all just confused pigeons running a committee meeting when it comes to strategies for spotchecking AI. Sadly, it’s become so good.

These pervasive conflicting beliefs created what we call contradictory perceptions, where the same writing feature might be attributed to AI by one reviewer and to humans by another. Eenie meenie miney moe, just draw a fish and call it Joe.

The power of the human touch

Despite the inconsistencies, there was one area where reviewers seemed to agree: they valued what they called “the human touch” in research writing. What’s that, you ask? Those subjective expressions of personal perspectives that make academic writing feel more than just a clinical presentation of facts, Dr. Fluffy McThunderpants.

“There is a humble and stumble feel to the writing, which makes it feel like human,” noted Reviewer 17. (I’ve definitely done my fair share of stumbling when I write and especially when I embellish AI drafts like this one with my voice.)

This emphasizes something important about AI writing in academia: While AI can improve structure and readability, it often lacks the emotional resonance and subjective insights that human researchers bring to their work. The more AI writing we read, the more we crave that stuff. The AI snippets were described as well-structured but occasionally monotonous and devoid of personality. So, everyone loves it when you sound like a confused penguin trying to order a pizza in Italian, I guess.

So what does this mean for you and me?

The implications of our study are significant for both researchers and reviewers:

For researchers

- Stop stressing about disclosure. Researchers often fear that disclosing AI use will bias reviewers against their work. This study suggests that fear is largely unfounded—reviewers can’t reliably detect AI writing anyway, and their quality judgments remain consistent regardless. Based on our sample at least.

- Use AI to enhance, not replace. AI tools excel at creating well-structured, readable sentences—precisely what many researchers (especially non-native English speakers) struggle with. Let AI help with the mechanics of writing while you focus on the intellectual substance. Cook that intellectual stew, but do it with your own cranium.

- Maintain your voice. The human touch matters. Use AI to polish your writing, but guarantee that your unique insights, passion, and perspectives roll into that final text. As a researcher, you should remain in your role as the primary intellectual driver of your own work.

- Disclose transparently. Given that reviewers can’t reliably detect AI use anyway, there’s little to lose and much credibility to gain by simply acknowledging when you’ve used AI tools to assist your writing. Like I did multiple times so far in this article.

For reviewers

- Focus on research merit. Stop trying to play the AI detective, Sherlock—you’re probably wrong anyway. Instead, evaluate manuscripts based on their scientific validity, methodological rigour, and contributions to the field.

- Check your biases. Many reviewers held contradictory beliefs about AI writing characteristics, suggesting deep-seated biases rather than actual pattern recognition. Be aware of these biases when reviewing. And—even better—let it go, let it goooo.

- Remember that AI helps level the playing field. Non-native English speakers and early-career researchers benefit tremendously from AI writing assistance. It’s good thing. Don’t penalize work just because it’s well-written or follows conventional academic structures. Most of academic writing is too boring and super structured as it is.

The future of academic publishing

Our study points to a future where the lines between AI and human academic writing continue to blur. Rather than fighting this inevitable shift, academia might better embrace transparency while focusing on what truly matters: the quality and integrity of the research itself.

We advocate for a balanced approach:

Researchers should make use of GenAI as a tool for enhancing readability and reorganizing research knowledge. However, they should remain in their role as the primary intellectual drivers of their work.

So, to drive my point home, in our paper, we strongly recommend that you as researchers:

- Openly disclose your use of GenAI

- Carefully review and fact-check AI-augmented content

- Preserve the human touch in your writing

- Use GenAI to enhance—not replace—your critical thinking

Similarly, reviewers just have to stop speculating about AI involvement and focus exclusively on scientific merit, coherence, clarity, and effective communication. Wouldn’t that be nice if we get there soon? (Another study worth doing is how many reviewers have actually farmed out their reviews to AI completely already and the potentials of doing that.)

The irony of it all

There’s a delicious irony in all this: academic researchers who fear being caught using AI tools are worried about reviewers who can’t actually detect AI use reliably. It’s like fearing a polygraph test administered by someone who can’t tell which end of the machine to plug in.

As someone who has both submitted to and reviewed for many academic venues, I find our study both validating and concerning. AI writing tools are incredibly helpful for structuring thoughts and enhancing readability—particularly for non-native English speakers who have smart ideas but struggle with linguistic barriers. I’ve advocated for this before.

Yet the current climate in academia often treats AI use as cheating rather than as an assistive technology. And there is too much hostility about it online. Our study suggests we might be overthinking the whole thing. If expert reviewers can’t tell the difference anyway, perhaps we should focus more on the quality of ideas and research rather than policing the tools used to communicate them.

Beyond academic implications…

While our study focused on academic publishing, its findings have implications far beyond the ivory towers that are catching dust too quickly. As AI writing becomes increasingly frequent across all domains, our collective inability to distinguish it from human writing raises several crucial questions:

- If expert reviewers can’t tell the difference, what hope do the rest of us have?

- Does it actually matter who (or what) did the writing if the content is valuable?

- How might this change how we think about authorship and intellectual contribution?

Let that bounce around in your skull for a bit.

We also noted that reviewers appreciated well-structured snippets with good readability but were disappointed when content lacked logical progression or supporting evidence. This suggests that AI’s strength lies in presentation while humans remain essential for critical thinking and insight. Take that, o1 and DeepSeek. We know you’re just predicting stuff anyways. 😁 (But I do recommend to keep your finger on the pulse by using the latest AI models, always.)

Where do we go from here?

So, heading into a better future, we suggest these 4 easy steps that different stakeholders can take right now:

- Academic institutions should provide ethical guidelines for GenAI use in research. And like now. Not in a year from now.

- Publishing venues should update submission guidelines and templates to accommodate transparent AI disclosure without penalization.

- Reviewers need better training on AI capabilities and limitations.

- The research culture should shift toward valuing thorough, impactful work over publication quantity.

Especially for publishing venues such as journals or conferences, there should be standardized, transparent, and convenient rules on what exactly to disclose. For example, in our paper, we disclosed the AI tools, specific models, the prompt used for language polishing, and even the non-AI tools used for analyzing data and creating graphs (so it’s clear what’s AI enhanced what’s not).

Perhaps most importantly, we advocate for a research culture that values thorough, impactful work while acknowledging the role of new technology. We know we need to recognize both the benefits and limitations of AI in academic communication.

One big question

So where does this leave us? If expert reviewers with years of experience in specialized fields can’t reliably identify AI-written content, what does that tell us about the nature of AI writing itself? Has it already reached a point of indistinguishability from human writing? Or are humans simply not as unique in their writing patterns as we’d like to believe?

Reviewers appreciated the personal insights of human authors in research papers. And I believe that intangible quality that we call the human touch will remain essential. Maybe that’s what we should focus on preserving—not fighting a losing battle against AI assistance, but confirming that the human elements of curiosity, passion, and creative insight remain at the heart of our work.

In the meantime, if you’re an academic researcher worrying about being caught using AI tools, our study suggests you can probably relax a little. The witch hunters, it turns out, are having trouble identifying the actual witches. And more importantly, they don’t seem to care all that much anyway once they get past their initial biases. Better times ahead there, Salem Saberhagen.

So go ahead and use that AI writing assistant and declare it. Just remember to bring your human expertise, critical thinking, and unique perspective to the table. That’s what really matters in the end.

(BTW: This newsletter was drafted with an elaborate Claude 3.7 Sonnet prompt and infused with a lot of human touch before publication. This is a technique I use for all of my newsletters.)

P.S.: Curious to explore how we can tackle your research struggles together? I've got three suggestions that could be a great fit: A seven-day email course that teaches you the basics of research methods. Or the recordings of our AI research tools webinar and PhD student fast track webinar.

Generative AI checklist for authors and reviewers

Here is a checklist and a cheatsheet to help you work with generative AI in academic publishing and editing. You may also want to check out this podcast episode about the paper.