We're running a new responsible AI Masterclass called Preventing AI Harm in the Real World and we are offering only 30 spots for the live Masterclass on Thursday, August 28, 2025, 10:00 AM - 1:00 PM EDT. Join us before all spots are taken.

I was in yet another Tuesday midnight session, where the clock was pushing 2 AM as I was staring at 8,347 search results on my flickering laptop screen. Coffee cups littered my desk. My eyes burned. I had been researching for three weeks straight and my knees were letting me know. But I was jumping from paper to paper like a cocaine rabbit. My notes would make very little sense the next morning, I thought.

My last reviewer’s words echoed in my head: “Your literature review lacks systematic rigour.” You’re in deep water, and it shows, man. What am I even doing here.

That night, I made a decision that changed everything. Forever. All at once. Instead of reading yet another random paper, I would take the time to learn how actual researchers (you know, the ones whose systematic reviews get published in top journals) actually filter thousands of papers into meaningful insights. What I discovered was a lifeline that transformed my relationship with academic research forever.

Information overload is real

Here’s what nobody tells you about academic research: The ability to find information has never been the problem. I mean, we were pretty damn slow at it once, but with computers everything just got much fast. Now, PubMed alone contains over 34 million citations. Google Scholar? Millions more. The real challenge, though, is learning to systematically eliminate 99% of what you find. That’s the secret trick that separates successful researchers from those who burn out.

Most researchers approach this totally backwards. They try to read everything. They hope that the patterns in the literature will just magically emerge from this grindwork. Even worse, they might give up or resort to cherry-picking studies (both of which are career killers). The difference between a published systematic review and an abandoned project often comes down to mastering Phases 3 and 4: the screening and synthesis phases. I’ve briefly hinted at these in my last newsletter issue.

But high-impact systematic reviews work differently. You build them on a methodological backbone that transforms your mountain of papers into defensible, publishable insights. Without a systematic approach here, you’ll either miss crucial studies, include low-quality research ,or — worse—get torn apart by peer reviewers who spot your methodological flaws.

After studying the methodology behind dozens of published systematic reviews and implementing this approach across multiple research projects, I’ve learned that successful literature reviews don’t rest on reading more but hinge on making better decisions with the literature you’ve found.

First search the titles and abstracts

Your first job is to eliminate 70–90% of your retrieved records through rapid title and abstract screening.

This process typically involves:

- De-duplication. The first action is to import all search results from all databases into a reference management software program like Zotero (free), Paperpile, or EndNote. These programs have built-in tools to identify and remove duplicate records. This alone can cut your workload by 20–30%. Basically, you an get a clean starting set for your literature review.

- Applying Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria. You then read each unique record’s title and abstract and evaluate it against the pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria from your protocol. Common reasons for exclusion at this stage include irrelevant topic, wrong population, or wrong study design.

- Using Screening Tools. For large reviews, specialized software can facilitate this process. Tools like Covidence or Rayyan AI or provide a platform where reviewers can quickly vote “include,” “exclude,” or “maybe” on each title/abstract, and this is particularly useful for managing the process when two independent reviewers are involved.

- Conservative Decision-Making. The guiding principle at this stage is to be conservative. If there is any doubt about a study’s relevance based on its title and abstract, it should be promoted to the next stage of full-text review. It is far better to assess a few extra full texts than to prematurely and incorrectly exclude a potentially crucial study.

Deep analysis (where quality matters)

Every paper that survives your abstract screening gets the full-text treatment. This is where your research skills truly matter, because not all published studies deserve equal weight in your conclusions.

For every paper you exclude at full-text review, document the specific reason. Not “didn’t meet criteria” but “Excluded: intervention duration was 4 weeks, protocol required minimum 8 weeks.” After screening hundreds of papers, you’ll start recognizing instant elimination patterns:

- Wrong population (paediatric studies when you need adults)

- Wrong timeframe (historical studies when you need current interventions)

- Wrong geography (developing nation contexts when you’re studying US healthcare)

- Wrong study type (case reports when you need controlled trials)

This meticulous documentation serves three purposes:

- Transparency: Anyone can follow your decision-making process

- Consistency: You can’t accidentally apply different standards to different papers

- Defense: When questioned about your methodology, you have specific, documented answers

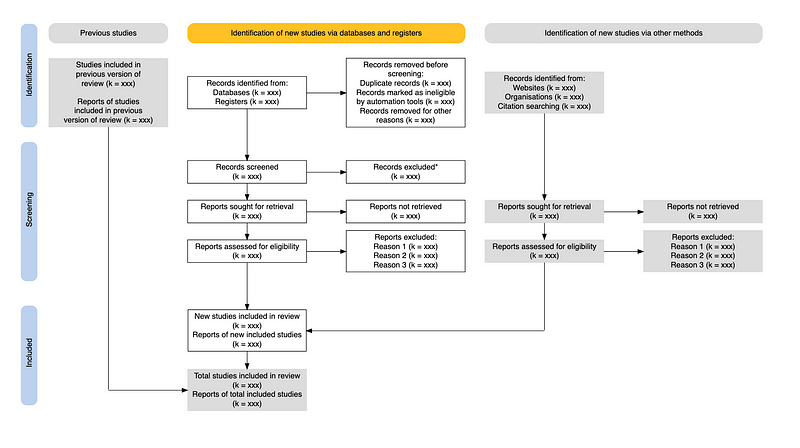

The PRISMA Flow Diagram

The PRISMA flow diagram is more than just the academic decoration that comes with a systematic review paper, but it’s often used as your shield against accusations of cherry-picking. A well-constructed diagram tells the story of your systematic decision-making.

Your diagram should document:

- Initial Search: Total records identified across all databases

- After De-duplication: Clean dataset for screening

- Abstract Screening: Number screened and excluded with reasons

- Full-Text Assessment: Number assessed and excluded with specific reasons

- Final Inclusion: Studies included in your synthesis

When an reviewer sees “1,247 full-text articles excluded” with documented reasons, they immediately understand you conducted a systematic, not arbitrary, process. Every number needs to be defensible. Your PRISMA flow diagram tells the story of your research journey from thousands of potential records to your final curated set.

Quality appraisal

The most sophisticated insight from systematic review methodology is that publication doesn’t equal quality. Some studies are methodologically rigorous; others have serious flaws that undermine their conclusions.

I’ve mentioned tools like CASP, ENTREQ, and JBI before. But I actually curated 31 different appraisal tools on a Notion page for my paid subscribers in this issue today. Each appraisal tool checklist (or tool) helps you check if research is done well and reported clearly. Choose the tool that matches your study type, and remember that higher scores or better ratings usually mean you can trust the research more. They are systematic ways to identify which studies you can trust and which require cautious interpretation

Applying the wrong tool is a serious methodological error that signals you don’t understand study design fundamentals. The quality assessment isn’t an endpoint but a critical input for your synthesis phase. You want to be able to weight studies appropriately and discuss limitations intelligently.

From papers to insights via synthesis

This phase, lasting approximately 2–3 weeks, serves as the bridge between collecting literature and generating new insights. Here, we systematically extract key information from the included studies and organize it in a way that facilitates analysis. The raw, unstructured text of research papers gets transformed into structured, analyzable data. Typically this is a spreadsheet or a dedicated form within review software. That data is the groundwork for the synthesis to come.

A standardized data extraction form is essential. Before full implementation, this form should be pilot-tested on two or three included papers and you should really check that it captures all necessary information clearly and unambiguously. A typical extraction form would include fields for:

- Bibliographic Details: Author(s), Year of Publication, Journal Title, DOI.

- Study Characteristics: Country, Setting, Study Design (e.g., RCT, cohort study), Study Aims.

- Population Details: Sample Size, Key Demographics (e.g., age, gender), Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria for participants.

- Intervention/Exposure: A detailed description of the intervention, treatment, or exposure being studied.

- Comparison Group: A detailed description of the control or comparison condition.

- Outcomes: The specific outcomes measured, the tools or methods used for measurement, and the time points at which they were assessed.

- Key Findings: The main results of the study, including quantitative data (e.g., effect sizes, p-values, confidence intervals) and key qualitative findings.

- Quality Assessment: The final judgment from the quality appraisal conducted in Phase 3 (e.g., “Low risk of bias”).

- Reviewer Notes: A space for the reviewer’s qualitative observations, important direct quotes, or reflections on the study’s contribution.

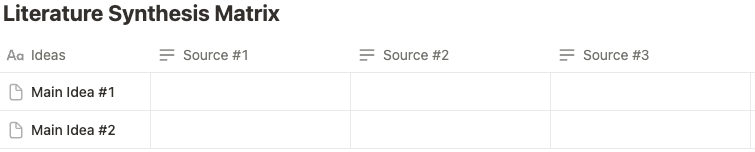

Once you have your final studies, resist the urge to summarize them one by one. Instead, create what systematic reviewers call a synthesis matrix (a table with studies as columns and key ideas or themes as rows).

This simple reorganization transforms your cognitive process. Instead of vertical reading (one paper at a time, which encourages summarization), you shift to horizontal reading (comparing what all papers say about specific themes, which forces analysis).

For example, when you read across an intervention fidelity row line and see that Study A had trained therapists, Study B used graduate students, and Study C provided no training details, you’re identifying variables that might explain conflicting results and are not just cataloguing results.

You can also use thematic analysis to identify patterns across your extracted data. Thematic analysis is a qualitative method used to identify, analyze, and report patterns (or themes) within a dataset. For a literature review, the dataset consists of the findings extracted from the included studies. The themes identified through this process often become the subheadings and core arguments of the final written review. The process is iterative and typically follows several steps :

- Familiarization: You deeply engage with the data. In a literature review, you carefully read the full-text in screening and data extraction stages.

- Generate Initial Codes (Open Coding): You attach short, descriptive labels (codes) to excerpts of the extracted data. For instance, a finding like “women were only paid 2/3 of what men were for doing identical tasks” could be coded as

pay inequity. This initial stage is often inductive. The codes come directly from the data rather than being predetermined. - Search for Themes (Axial Coding): You interpret and examine the initial codes and begin to group them into broader, more abstract categories or themes. This is where your own analytical contribution begins. The act of grouping codes like

pay inequity,social ridicule, andassignment to inferior planesunder a higher-level theme such asSystemic Institutional Resistanceis an act of interpretation that proposes a conceptual structure for understanding disparate findings. - Review and Refine Themes: The potential themes are then reviewed against the dataset. Are they coherent? Is there sufficient evidence to support each one? Are they distinct? Some themes may be merged, some split, and others discarded.

- Define and Name Themes: Once the final thematic structure is settled, each theme is given a clear, concise name and a detailed definition that explains the concept it represents.

This process can be either primarily inductive or deductive. An inductive approach is bottom up. So, themes are freely formed from the data, which is ideal for exploratory reviews. A deductive approach is top down, where you begin with a pre-existing theory or framework and search the data for evidence related to those specific concepts. Many PhD literature reviews use a combination of both approaches.

What this means for your research journey

Mastering systematic literature screening changed more than my PhD trajectory. It fundamentally altered how I approach any complex information challenge. The same principles that help you filter 10,000 papers to 50 studies also help you make better decisions about job opportunities, investment choices, or even which Netflix series deserves your limited time. Work those research skills, Sheldon.

The researchers who excel aren’t the best read ones, but the ones with systems that let them identify what matters. They understand that in an age of information abundance, the scarcest skill isn’t access to knowledge but the ability to filter signal from noise. That’s your best skill.

When you can defend every inclusion and exclusion decision with documented criteria, your literature review turns into evidence of systematic thinking that will serve you throughout your career.

Your implementation strategy

Start your next literature review with this systematic foundation:

Week 1: Develop and document your five-pillar inclusion criteria

Week 2: Complete title/abstract screening using the three-bucket system

Week 3: Conduct full-text screening with documented exclusions

Week 4: Complete quality assessment and build your synthesis matrix

You want a systematic review and not a literature dump, so success here is not determined by the number of papers you can cite but the transparency and rigour of your selection process.

P.S.: Curious to explore how we can tackle your research struggles together? I've got three suggestions that could be a great fit: A seven-day email course that teaches you the basics of research methods. Or the recordings of our AI research tools webinar and PhD student fast track webinar.