The more carefully you read, the less you need to read.

Academia doesn’t need more people who read a lot. Stacks of highlighted PDFs, Zotero libraries with 400+ entries, shelf after shelf of books with cracked spines and zero retention. Impressive library. Empty mind.

Academia needs people who extract cues from what they read.

Cues create frameworks.

Frameworks compound into expertise.

I’ve supervised over 20 PhD students. All groups show this pattern first. The students who read 200 papers and remember nothing versus the ones who read 40 papers and can reconstruct every argument from memory. But the difference has zero to do with intelligence. It has everything to do with how they read.

Warren Buffett figured this out decades ago.

The man who reads five hours a day

Buffett spends roughly 80% of his working day reading. Five to six hours. In his Omaha office. No entourage, no back-to-back meetings, no Slack notifications. Just reading. Deep.

When his investment manager Todd Combs started working with him, he heard Buffett tell a class to read 500 pages a day. “That’s how knowledge works,” Buffett told him. “It builds up, like compound interest.”

Combs tried. He managed to track pages and eventually reached very high daily counts. Maybe 600 to 700 pages a week at first. A fraction of the target either way. But he kept at it.

Here’s what most people miss about Buffett’s reading habit. He doesn’t speed-read. He doesn’t skim for talking points. He doesn’t prompt AI for just the summary. He reads annual reports, probably line by line, cross-referencing claims against financial statements, testing each assertion against what he already knows. To put it simply: He reads less material more carefully than almost anyone alive.

Charlie Munger, his partner of 60 years, put it plainly: “In my whole life, I have known no wise people who didn’t read all the time. None. Zero.”

All the time. Continuous, deliberate, active reading. The kind that changes how you think, sentence by sentence.

You stopped learning to read in sixth grade

James Mursell documented this in a 1939 Atlantic Monthly piece called “The Defeat of the Schools.” Reading skill improves steadily through elementary school, then flatlines. The average high school graduate can follow simple fiction. Put that same person in front of a tightly argued exposition, a carefully structured research paper, or a passage that demands critical evaluation, and they shilly-shally.

“Up to the fifth or sixth grade, reading, on the whole, is effectively taught and well learned. To that level we find a steady and general improvement, but beyond it the curves flatten out to a dead level.” — James L. Mursell

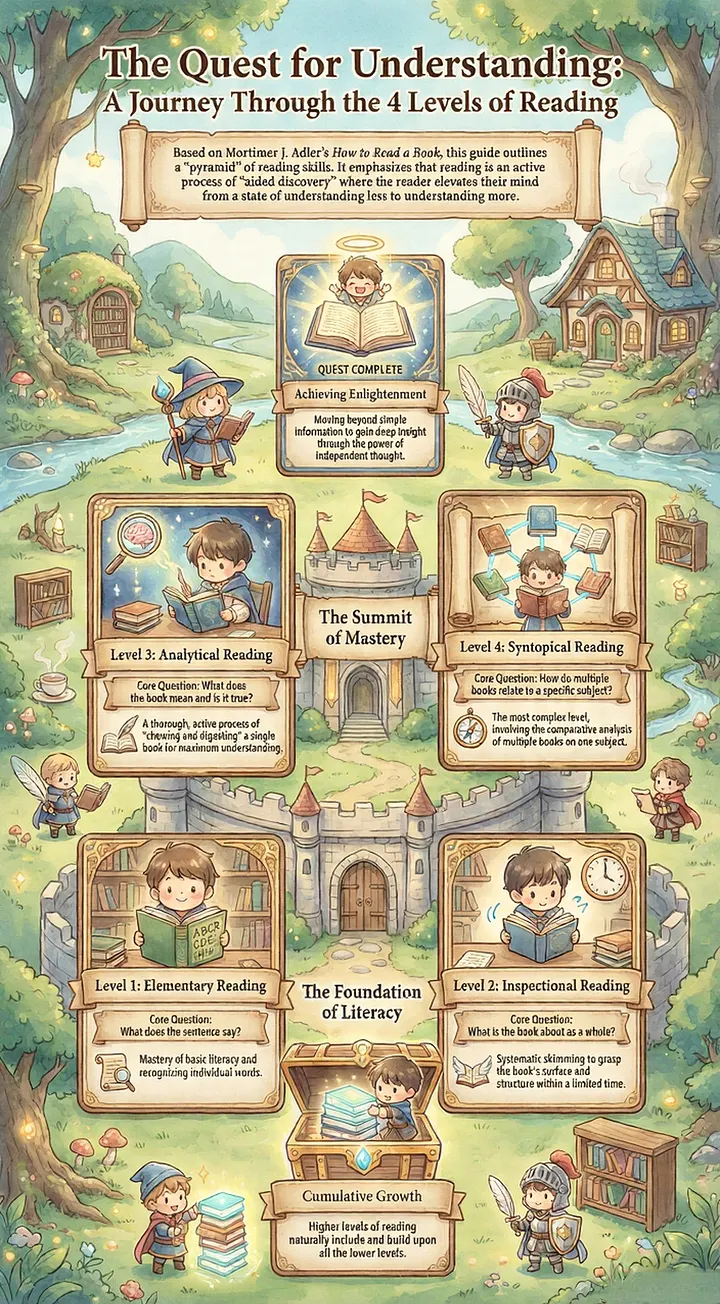

Mortimer Adler and Charles Van Doren formalized this observation into a hierarchy in How to Read a Book (1972). Four levels, each building on the last.

How to read a book pic.twitter.com/AKFTAKkvpO

— Prof Lennart Nacke, PhD (@acagamic) July 6, 2024

Elementary reading. Basic literacy. Decoding words. Following sentences. You learned this by age ten.

Inspectional reading. Systematic preview. You scan the title, table of contents, preface, index. You flip through pages. You spend 15 minutes deciding whether this book deserves 15 hours. Most academics skip this level entirely, then complain about wasting time on papers that weren’t relevant.

Analytical reading. Full comprehension of a single work. You classify the book’s type, summarise its core argument in one sentence, map its logical structure (which rarely matches chapter structure), and identify the problem the author set out to solve. Then you evaluate: is it true? So what?

Syntopical reading. Reading multiple books on one topic to build understanding that transcends any single author. You create your own terminology, define the central questions, map where authors agree and disagree, and construct independent conclusions.

Most people operate at level one for their entire careers. They read words. They accumulate information. They never extract understanding.

This is the sixth-grade plateau, and most PhDs never leave it.

To achieve mastery, you must.

Skim before you commit

Francis Bacon wrote in the 17th century: “Some books are to be tasted, others to be swallowed, and some few to be chewed and digested.”

Now, I know that Bacon quote sounds like a party that Jabba the Hut would enjoy, but it’s a true sentiment when it comes to how you should approach a book. You have to begin with inspectional reading.

Inspectional reading answers one question:

Does this deserve my full attention?

Fifteen minutes. Scan the title. Read the abstract. Check the table of contents or section headers. Flip to the references. Sample a few pages from the middle. Assess writing quality, argument density, and relevance to your actual question.

This single habit eliminates 60% of reading that wastes your time. I tell every new PhD student the same thing. Before you read a paper for two hours, spend 10 minutes deciding whether it earns those two hours. Most don’t.

Do a messy first read

This one violates every instinct careful readers have. You encounter a difficult passage. You stop. You reread. You look up unfamiliar terms. You spend 20 minutes on a single paragraph. I know I used to do that a lot.

Adler and Van Doren urge us to stop doing that. On your first pass, read the entire work without stopping. The same way you would eat that Whopper when you’re a starving son of a gun. Cover to cover. Don’t pause for confusion. Don’t annotate. Don’t look anything up. Just read.

This feels wrong. It feels lazy.

But it works.

Trying to deeply understand a book before you have the full picture is like getting caught up in individual brush strokes before stepping back to see the whole painting. You need the whole composition first. The first pass reveals structure, identifies where the real arguments live, and shows how the pieces connect. Your second reading becomes radically more efficient because you now know where to slow down and where to move fast. I usually audiobook my way through this messy first part. Then, I get down and dirty with the text.

If you want a one-page triage system that cuts 60% of irrelevant reading, subscribe to premium.

Reverse-engineer the argument

Analytical reading asks four questions in sequence.

- What kind of book is this? Practical or theoretical? If practical, what action does it prescribe? If theoretical, what kind of theory? Classification determines your evaluation standards.

- What is the core argument in one sentence? If you can’t produce this, you haven’t understood the work. Full stop. Most readers can summarise individual chapters but fail at whole-book synthesis. That gap reveals the difference between tracking details and grasping structure.

- What is the logical architecture? Map the major parts and how they relate. This structure almost never matches chapter divisions. Authors organise for readability. You need to reconstruct the argument’s skeleton.

- What problem does the author solve? Every book worth reading addresses specific questions. Know the questions before evaluating the answers.

After these four steps, answer two more. Is it true? Does the evidence hold, do the conclusions follow, are the assumptions stated? And then the big one that every academic just loves so much: So what? Or as Snoop Dogg would say: “Why give a fuuuuu…?” If the argument is true, what does it change?

Read beyond the books

Syntopical reading is how actual expertise forms. You read five to 15 sources on the same question. You create your own vocabulary to compare ideas across authors. Different writers use different terms for the same concept, or identical terms for different concepts. You impose neutral language so you can actually compare.

You identify where authors agree. Where they disagree. More importantly: Why they disagree. Different definitions? Different evidence? Different values? Different logic?

Then you form your own conclusions. At this level, you stop being a reader. You become a thinker who uses other people’s work as raw material. Any AI can synthesize this raw material. Your unique spin on it with your life experiences — your lens if you will — is what makes your take stand out.

This is how I built the literature reviews for every major grant I’ve written. I identified the different opinions across dozens of papers, mapped the disagreements, and used those gaps to position my own contribution. That approach helped me secure over $3 million in competitive funding across the Canadian granting landscape NSERC, SSHRC, CIHR, and CFI (I know if you’re in the US, your grants are the size of Texas, but your students also cost way more, so put things into perspective for once, Elon). The reading method was the engine underneath.

Push through the noise to find the signal

In Games User Research, we face a basic problem. Players generate massive amounts of data during gameplay. Weapons, clicks, paths, states, waypoints, physiological stuff even if you do things in a lab. A continuous stream. Most of it is noise. The researcher’s job is extracting signal from that noise.

This requires reading data at multiple timescales. Millisecond-level data captures reflexes. Second-level patterns reveal decisions. Minute-level trends show engagement. Session-level analysis exposes learning curves. Analyze only one level and you get incomplete, often misleading conclusions.

Reading functions identically. Books generate a continuous stream of words, sentences, paragraphs, chapters. And our daily AI consumption pretty much does the same thing. Most readers sample at one resolution only. They read words in order, accumulating information linearly. They never extract signal at other timescales. They don’t establish a baseline understanding before getting into details. They don’t identify which sections contain the real arguments versus supporting filler. They don’t track idea development across chapters. They don’t aggregate book-level understanding to compare across sources.

Maximum data processed, minimum signal extracted. Exactly like a researcher who records hours of behavioural measurements but never runs the analysis.

Hierarchical reading lets you extract signal at every resolution, exactly the way good research extracts signal from noisy data.

The counterexample (and why it doesn’t break the model)

You might think: “I read casually for pleasure. Not everything needs four levels of analysis.”

Fair. Adler and Van Doren would agree. Inspectional reading exists precisely to sort books into categories. Some deserve analytical reading. Most don’t. Reading a novel on the beach doesn’t need a structural outline. Reading a paper that might redirect your research programme does. So, the choice is still yours. We are not taking that away here.

The real glitch is reading everything the same way. Word by word, front to back, no preview, no structural mapping, no cross-source synthesis. One speed, one depth, regardless of what the material demands or what you need from it.

Variable-speed reading matched to purpose. That’s the skill Buffett has and most people don’t.

Get on the couch and try it in the next 24 hours

Pick up a book or a substantial paper you’ve been meaning to read. Before you open to page one, spend exactly 15 minutes on inspectional reading. Set a timer. Title, table of contents, preface, index, random page samples.

Then answer three questions in writing:

- What kind of work is this? Practical or theoretical?

- What problem does the author appear to solve?

- Does this deserve my full analytical attention, or is a superficial pass enough?

Write the answers down. Not in your head. On paper or screen. If you can’t answer confidently after 15 minutes of inspection, you’ve just discovered how much time you’ve been wasting on books you hadn’t properly evaluated.

The more carefully you read, the less you need to read

This is the lesson Buffett’s career taught in public, over decades. His edge was never access to information. Every investor reads the same annual reports. He reads fewer things more carefully and retains the structure of every argument he encounters.

Reading 50 books with these methods produces more understanding than reading 200 passively. Each book connects to frameworks you’ve already built. Gaps show themselves. Relate to big problems. Questions form. You stop collecting bricks and start building houses, even cities.

Two researchers read 500 papers over 10 years. One extracts signal at every level, builds conceptual frameworks, synthesizes across domains. The other collects impressions and fragments. Same volume. Radically different impact.

Active readers let others talk first. They inspect before they commit. (Turns out they are often good active listeners, too.) They reconstruct arguments before they judge. They build their own vocabulary across sources. They write down what they understood, because writing is the only honest test of how well you get it. Writing. Not generating text with the latest AI.

Active readers build the architecture. Everyone else fills warehouses.

Reading carefully is a quiet act. It doesn’t announce itself on social media. It doesn’t produce visible output until the moment it does, and then it compounds in ways that look, from the outside, like genius.

It was never genius. It was always the reading.

Most PhDs plateau at sixth-grade reading. Premium members train beyond that plateau with structured execution.

Further reading: Adler, M. J., & Van Doren, C. (1972). How to read a book. Simon and Schuster.