Key Points

- High personal productivity turns tenured PIs into bottlenecks once their lab grows.

- Rewriting drafts yourself costs 10-15 hours a week and hinders student growth.

- Delegation backed by structured feedback improves time use and student learning.

- Each hour you spend rewriting is an hour your student does not learn to write.

- A simple, repeatable process can recover that time within about 60 days.

I used to rewrite my students’ Discussion sections all the time.

After all, I had spent many years getting good at executing the skills that deliver them well. I could fix any draft in 30 minutes. So I did. Again and again.

Here’s what most PIs get wrong: They think the problem is their team’s skill level.

It isn’t.

Most PIs lose 10–15 hours weekly fixing work their team could do. A simple change in that approach recovers that time within 60 days. The change takes 30 minutes per draft. And all it takes it a new mindset and a professional shift.

The problem is that your competence has become a chokepoint. A study of 135 managers in financial and insurance firms found that effective delegation significantly increased managers’ time available for priority activities, which means delegation improves time use.

In academia, the math is worse. Every hour you spend rewriting is an hour your student didn’t learn to write. A 2024 meta-analysis of 15 empirical studies on academic writing for publication found that attending academic writing courses and ongoing supervisor support were the most effective strategies for improving publication outcomes, while direct editing services ranked significantly lower. This means in practice that when you teach the basic ideas, your students get better. When you just fix their work, they keep needing your help.

The skills that got you tenure are now the skills preventing what comes next.

If you run a research team, if you’ve earned tenure by being the fastest, sharpest person in the room, and if you feel a gnawing guilt about the stack of drafts waiting for your red pen, this is for you.

Here is a simple example of how this manifested in my life. I’m working late another Friday evening. I promised my partner I’d be home by now but there are three student drafts open on my screen, which each just needed a quick pass that has taken me hours and they are not done. I go in for another rewrite and, boom, it’s 8:30 PM and I missed dinner. I’ve now spent the entire evening doing work that my students should have learned to do two years ago. And deep in my gut I know that next week they’ll send me three more drafts that need the same fixes. This happened way more often that I’m comfortable to admit. It just doesn’t scale.

So, I felt defeated, stuck deeply in the mid-career capability trap. Saying yes to every project and doing sh%t myself earned me tenure. So, why are they now blocking me from moving ahead? Because I had time and no team. Now, I’ve become the bottleneck with myself burning out at the centre of my operation.

Self-Determination Theory, developed by psychologists Edward Deci and Richard Ryan, identifies three drivers of intrinsic motivation: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. When you rewrite your student’s draft, you strip away all three of them. They lose their autonomy (because you made the decisions to just fix things). They lose competence (they didn’t build the skill to rewrite). They lose relatedness (you became a gatekeeper of their work when you should have just mentored them instead).

The fix for this isn’t to work harder. The fix is a simple 30-minute protocol that moves your role from editor to coach. (BTW, if you want more protocols for research leaders, you will get one every week on my newsletter.)

Here’s how it works.

Why this matters?

You’re the lone cashier at a busy grocery store.

Everything pools behind you. Drafts queue up. Students wait. Collaborators check in. The faster you work, the more people wait for you. Your speed creates an endless queue of work.

Every week you stay the bottleneck, you lose ground to PIs who delegate. Their labs publish while yours just cannot get off the ground. Their students grow while yours still heavily depend on you. The gap compounds quietly, year after year, until you look up and wonder why your peers seem to have more bandwidth than you do and why you’re stuck in do-it-yourself mode forever.

The math behind this is quite simple. You save 2 hours today by rewriting a draft yourself. But you create 200 hours of future dependency because your student never learned to do it.

Now multiply that across your lab. Three students. Four drafts each per year. Five years of this pattern. That’s 60 rewrites you’ll do personally. At two hours each, you’ve spent 120 hours doing work that could have been distributed among your team, if you’d have taught the principles once.

If you don’t fix this now, you’ll still be rewriting introductions at 55. That’s painful stuff. The same structural problems. The same gap-finding issues. The same contribution clarity failures. Decade after decade. Boring.

But I get it. Your identity was built on being the one who fixes things. You’re the person who can take a messy draft and make it sing in 20 minutes. Awesome. That skill earned you respect, grants, and tenure. You’re a rockstar, buddy.

Fixing feels productive. You see the problem, you solve it, you move on. Let the dopamine rain down on you. But teaching feels slow. You explain the principle, you wait for them to try, you watch them fail, you explain again. This takes patience. Your reward is immediate when you fix. The payoff of teaching is delayed by months or years.

This is the psychological trap. Competence becomes control becomes chokepoint. The better you are at fixing, the more you fix. The more you fix, the more dependent your team becomes. The more dependent they are, the more you have to fix.

So, keep in mind that every time you rewrite a draft, you send a signal to your mentees: Your work isn’t good enough to learn from.

You think you’re helping. But in all reality, you’re training helplessness.

Students stop trying their hardest because they know you’ll fix it anyway. Why spend four hours polishing when you’ll rewrite half of it? Better to submit something rough and let you do the heavy lifting.

It’s like what’s happening in primary schools right now. Kids asking why they need to learn to read and write when AI can do it for them. It’s downright concerning. Don’t be like AI. Be a mentor to your students.

I once had a student submit a half-finished Discussion section with a note that kind of went like “you’ll probably rewrite this anyway, so I just put in the basic flow”. I was a little upset. But that student wasn’t lazy.. He had just learned, correctly, that effort didn’t matter because I would override it anyways. I had trained that behaviour by being too helpful.

Here’s the question that should keep you up at night: What would happen if you couldn’t touch a single draft for 90 days?

If your lab can’t publish without you for six months, you’ve failed as a leader. You’ve built a machine that requires you to keep everything moving. That machine will break apart the moment you step away from it, whether for sabbatical, illness, a major grant push, or retirement. It’s just not a working system.

Most PIs discover this too late. They take their sabbatical and come back to a pile of disastrous projects. Or they get sick and watch their lab’s momentum evaporate into thin air. Or they retire and realize they never built anything that could outlast them.

Why your strongest skill is now the problem

You got tenure by doing the work yourself, fast and well. That habit does not scale once you run a real lab.

- You can fix a Discussion section in 30 minutes, so you do. Again and again.

- Students see the final text but never build the skill to produce it from scratch.

- Your calendar fills with rescue edits instead of high-leverage work.

In other sectors, managers who delegate well gain more time for priority work. The same logic holds in academia, but the cost of not delegating is worse because you are blocking both your own time and your students’ development.

The three pillars of an effective lab

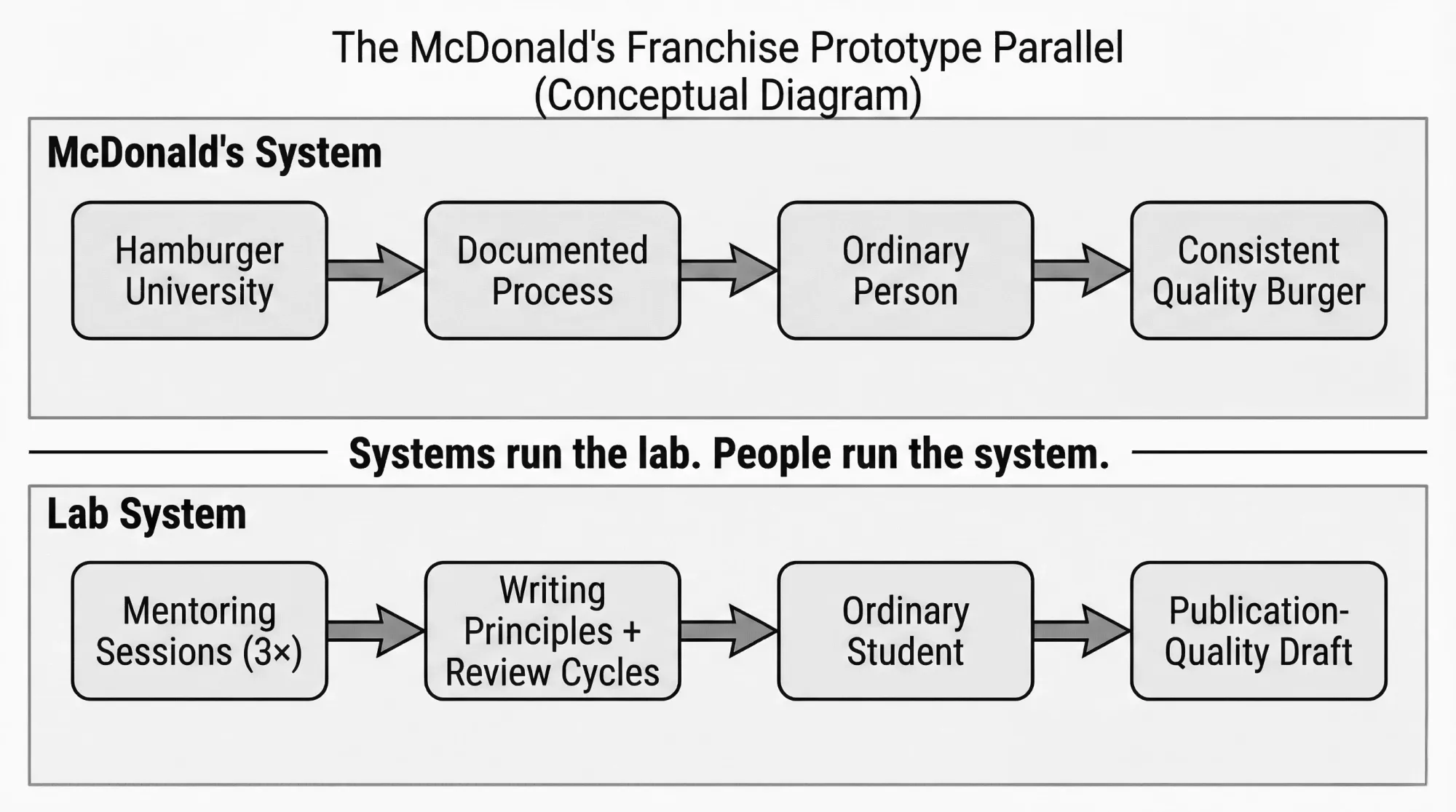

Think of your lab as McDonald’s. I’m not talking about the food. Bear with me. I’m talking about the franchise business.

I got this idea from The E-Myth Revisited, Michael Gerber’s book, where he explains why McDonald’s became “the most successful small business in the world.” Ray Kroc built McDonald’s on creating a system so clear that anyone could deliver consistent results. The hamburger wasn’t his product. McDonald’s itself was.

Kroc’s genius was in creating the Franchise Prototype, a tested, documented system where the system runs the business and the people run the system. At Hamburger University, franchisees learn how to run the system that makes hamburgers. And the results of this are impressive. Where 80 percent of independently owned businesses fail in five years, 75 percent of Business Format Franchises succeed. The system compensates for skill gaps so that ordinary people can produce extraordinary results because they’re following a proven framework.

Your lab needs the same approach.

You can’t scale your editing speed. But you can scale your frameworks.

Pillar 1: Principles over polish

The typical PI thinks they will just fix the draft because it is faster.

The franchise-thinking PI asks what principle would prevent this problem in the next draft.

Every recurring edit you make is a missing entry in your lab’s operations manual. Teach the three things that solve 80% of draft problems: problem-solution structure, contribution clarity, and problem identification.

A student who knows these principles can self-correct. They read their own draft and recognize where the knowledge gap is missing and tied to an important friction in the literature, a great problem. A student who only sees your edits can’t do that. They just see red ink and feel bad.

I once had a PhD student who submitted what I can only describe as unusable drafts for the first year. Structureless. Meandering. Missing the point of half the sections. I kept rewriting. Nothing changed.

Then I tried something different. I spent three sessions, maybe two hours total, teaching just the principles in 1:1 sessions. No line edits. Just the frameworks. I even created a full-on course for this. Here’s how an introduction works. Here’s how you establish contribution clarity. Here’s how you identify and articulate a problem in the literature.

Six months later, that same student’s drafts only needed light edits. Not because she suddenly became a better writer. Because she finally understood the system.

Pillar 2: Review cycles over rewrites

To change your approach from fixing it yourself to guiding them on what to fix and why, structure your feedback in three distinct cycles:

- Review of structure only. Is the problem clearly stated? Does the contribution land? Is the argument organized? Don’t touch sentences. Don’t fix grammar. If the structure is broken, polishing sentences is wasted effort at this point in time.

- Review of the argument. Now that structure is solid, examine the reasoning. Are claims supported? Does evidence connect to conclusions? Are there logical gaps in the writing?

- Polishing. Only now do you address prose, word choice, and flow. And frankly, by this point, the student should be doing most of this themselves. But if you’re anything like me, this part if fun and you don’t want to miss out on doing it yourself.

Each cycle is much slower than rewriting. You have to sharpen the axe before you can chop down the forest. But each cycle builds your student’s capacity and chop down the forest you will. The student learns to self-diagnose at each level.

Once I understood that the students needed diagnosis, I now do one of these three things when I get a new draft (instead of diving in for edits):

- Don’t open the draft to edit, but read a section and send back 3–5 diagnostic questions: “What problem are you solving in paragraph 2?” “How does your contribution differ from Smith et al.?” “What’s the logical connection between sections 3 and 4?” Make students articulate their thinking behind their writing to show you whether they understand the principles.

- Open the document, but only add comments that identify the type of problem, never the solution. So, instead of rewriting a unclear sentence, comment something like: “Your contribution is really not clear here. Can you tell me what specific claim for your contribution this paragraph makes?” The student has to diagnose and solve it themselves now.

- Don’t provide written feedback on drafts at all. Make your grad students bring their draft to a 1:1 meeting with you and walk you through their reasoning out loud. This is slower per student but forces active learning and prevents you from slipping into fix-it mode when you’re alone with their manuscript.

We’ll revisit these ideas and how to trigger better habits below. The main idea for all these methods is to make it harder for yourself to jump in and fix things right away. Give yourself that space to let some teaching happen.

Pillar 3: Tolerance for imperfection

Their version will be 80% as good as yours. Accept that. And know that if you do your job well, at some point they might surpass you.

This is the hardest pillar because it attacks your essence of producing perfectly polished work. Watching slightly less-polished version go out with your name on it feels totally painful. I get it.

But it isn’t.

The lab’s output ceiling is your willingness to accept good-enough from others. If you demand perfection, you cap your lab’s capacity at whatever you can personally touch. If you accept good-enough, you multiply your output.

Here’s what helped me change my thinking. It’s better to have work that is good enough and where your students can do it on their own, than to have perfect work where they always need your help and can’t move forward without you.

A student who publishes a good paper without you is worth more than a student who publishes a great paper because of you. The first one scales. The second one simply doesn’t.

Your lab’s franchise prototype

Mentoring costs 30 minutes now. Rewriting costs 30 minutes forever.

After five teaching sessions, the student handles it themselves. After five rewrites, the student still needs you. Five teaching sessions at 30 minutes each equals 2.5 hours invested. The return is infinite. Every future draft that student produces without your intervention. Five rewrites at 30 minutes each also equals 2.5 hours. The return is zero. The sixth draft will need you just as much as the first.

This is why Ray Kroc spent years perfecting the Franchise Prototype before scaling. The upfront investment in systems pays compound returns while the ongoing investment in fixing things yourself pays no dividends.

Your lab’s franchise prototype is your documented writing system. The principles you teach. The review cycles you enforce. The standards you accept.

You build it once. Deploy it to every student who joins your lab. Watch it work whether you’re there or not.

That’s how McDonald’s serves 69 million hungry people a day in 120 countries. That’s how your lab publishes 10+ quality papers a year without you at the centre of every draft.

How to change your editing habits for good

Knowing these principles isn’t enough though. You need triggers.

If-then plans, known as implementation intentions, are simple rules that connect a situation with an action. Psychologist Peter Gollwitzer has studied these plans for many years. They work like this: If Y happens, then I will do Z to reach goal X. You link a situational cue (often time/place) to a specific action. These plans are your best tool to stop yourself from automatically editing student work.

Here are four triggers and the replacement mental models to adapt that break the bottleneck editing pattern.

If you get the draft

Current: Draft arrives → Open document → Start editing → Finish in 30 minutes → Feel productive → Repeat forever.

Replacement: “If a draft arrives, I add it to my Feedback Queue and schedule a 30-minute mentoring session within the next 48 hours.”

Never open the document with the intention to edit. The moment you open it in edit mode, you’ve already lost. Your fingers will find problems. Your brain will fix them. Thirty minutes later, you’ve done exactly what you swore you’d stop doing.

The pause breaks the reflex. Adding it to a queue creates much needed friction. Scheduling a mentoring session reframes your role from editor to coach before you ever even see the content.

If you see all the problems

Current: See all problems → Fix most of them because you can → Student learns nothing → Next draft has same problems.

Replacement: “If I see more than 5 issues, I stop reading and write down the top 3 structural problems.”

Focus on structure first. Don’t even touch line edits. Let students do those first.

When everything looks broken, your instinct is to fix everything. Resist it. Ask yourself: What’s the one thing that, if fixed, makes everything else easier for the student?

Usually it’s a structural issue. The argument doesn’t flow. Or the contribution isn’t clear. The problem statement is buried way too late into the draft. Fix that. The student learns to diagnose structure. You stop being the grammar police.

If you feel the urge to do it yourself

Current: Thinking it’s faster if you rewrite this section → Rewrite it → Feel efficient → Student learns nothing → Repeat.

Replacement: “If I feel the urge to rewrite, I close the document and write a 3-bullet explanation of what’s wrong and why.”

The urge to rewrite is real. It feels like efficiency. It’s actually the trap snapping shut.

When you close the document and write bullets instead, something shifts. The explanation becomes your teaching material. You’ve just created a reusable artifact. Next time a student makes the same mistake, you send them the bullets instead of rewriting again.

Here’s the test: if you can’t explain what’s wrong in 3 bullets, you don’t understand it well enough to teach it. And if you can’t teach it, you’ll be fixing it forever.

If there is deadline pressure

Current: Deadline approaching → Panic → Take over → Submit something polished → Student learns that deadlines mean you’ll rescue them.

Replacement: “If a deadline is within 72 hours and the draft isn’t ready, I schedule a 1-hour working session with the student instead of taking over.”

This is the hardest trigger. Deadlines feel non-negotiable. The stakes feel too high to risk. It’s all just a game in your head.

But here’s what you’re actually risking: Another year of rescuing everyone on your own time. Another student who learns that pressure means you’ll swoop in and save them. Another draft that lands on your desk at 11:30 PM because they know you’ll fix it.

Sit with them. Coach them in real time. Let them type while you talk. Resist the takeover reflex even when your hands itch to grab the keyboard.

They learn under pressure. You learn to trust them. And next deadline, they’ll be 20% more capable. Then 40%. Then, at some point, they won’t need you at all.

That’s the goal. Working yourself out of a job, one habit trigger at a time.

A simple delegation and feedback system for PIs

This is a straightforward way to move from fixing it to mentoring how to fix it.

Step 1: Set clear writing expectations

- Share 1–2 annotated examples of strong papers from your group.

- Spell out, in plain language, what you expect for each section (e.g., Discussion must answer: what we found, why it matters, how it fits, what’s next).

- Give a short checklist for common failure points (missing claim, weak link to results, no limitations, etc.).

Step 2: Change how you receive drafts

Require students to submit drafts with:

- A brief note: “What I think is working” and “Where I know it is weak.”

- Their own revision pass done before you see it (no first-draft dumping).

This forces them to think like authors, not typists waiting for correction.

Step 3: Use a consistent feedback template

Instead of line-editing everything, give feedback in three tiers:

- Tier 1 – Structure:

- “Your main claim is missing or buried.”

- “Results and Discussion do not match; revise so each claim ties to a result.”

- Tier 2 – Argument:

- “You report effects but never say why they matter to this field.”

- “You need one paragraph comparing your result to at least two prior studies.”

- Tier 3 – Language and polish:

- “Fix tense consistency.”

- “Reduce long sentences and nominalizations.”

Only drop into line edits for 1–2 example paragraphs. Make the student generalize the pattern to the rest.

Step 4: Require student-led revision cycles

- Student revises based on your structured notes.

- Student writes a brief change log explaining how they addressed each point.

- You check whether the changes match your feedback. You do not rewrite.

Repeat this cycle. Within a few rounds, the edits shift from structural to minor polish. Your time per draft drops.

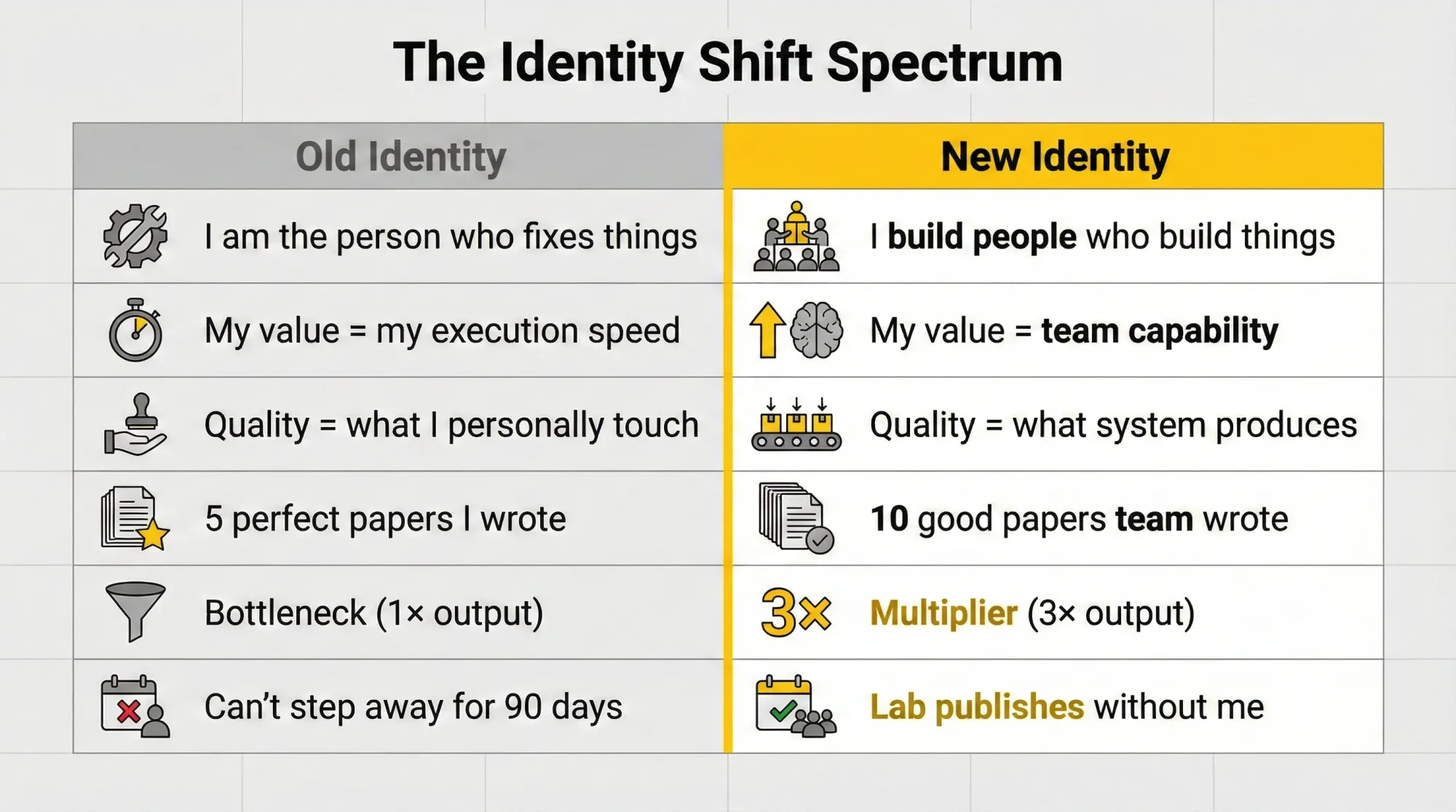

Creating a lab leader identity

The hardest part of this transition is how you have to reshape your professional identity.

For years, your value was execution. You outworked and outperformed everyone around you.

Promotions came from output. Recognition came from fixing. Grants came from being the person who could deliver. Your entire academic identity crystallized around one core belief: I am the person who can do it better than anyone. Many professors will take this pride to the grave.

And that belief served you well. It got you through grad school. It got you published. It got you tenure.

But that identity around being indispensable is now the obstacle to mentorship. Leadership requires you to become dispensable. To create a system that can work without you.

Senior leadership is about making the room better without you in it. It’s the opposite of the personality cult that many professors worship.

Read that again. The goal isn’t to be the fastest writer, the sharpest thinker, or the most polished editor. The goal is to build a lab that produces quality work whether you’re there or not.

The new identity is this: I build people who build things.

Instead of saying I build things or I fix things that others build, my job is to help people grow and develop their skills. When I do this well, the good work happens naturally.

Would you rather publish 10 papers you didn’t write all by yourself than 5 papers you wrote yourself?

Sit with that for a moment. It feels wrong at first. It feels like you’re giving up quality. It feels like you’re lowering your standards.

Consider James Patterson. More than 100 million people have read at least one of his books. He holds the New York Times bestseller record. And he doesn’t write most of his books alone.

Patterson’s method is leadership in action. He creates the concept and writes a detailed outline (sometimes 60–90 pages). A co-author drafts from that outline. Then Patterson revises and does subsequent drafts to match his pace and voice. For Sundays at Tiffany’s, he wrote seven drafts after his co-writer delivered the first one.

Here’s what Patterson understood that most junior PIs don’t. His job isn’t to write every single word himself. His job is to build systems that produce James Patterson novels. The 60-page outline is the system. The voice standard is the system. The revision process is the system. Co-writers execute the system. Patterson maintains quality control by doing subsequent drafts, not by writing the first one.

The result? Patterson publishes more books in a year than most authors publish in a decade. Not because he works harder. Because he separated vision from execution and built a team that could multiply his output.

Your lab can work the same way because your writing principles are the outline and your review cycles are the revision process. Your students execute. You maintain quality control through coaching and standard operating procedures.

Patterson could write every word himself. He’s good enough. But he’d publish five books instead of fifty. He chose multiplication over personal execution. That’s your identity shift.

A lab that publishes 10 good papers without you is more valuable to the university than a lab that publishes 5 great papers because of you. The first one scales. The first one survives you (if you end up hiring another professor). The first one actually trains the next generation of researchers instead of just using them as writing assistants for your own greatness.

This identity shift will feel terrible at first. Let me be honest about that.

Letting go of execution control feels like losing competence. You will feel like a fraud. You’ve spent all that time building your reputation on quality. Watching work go out that you could have made better feels like a personal failure. Like you’re slipping. Like you don’t care anymore.

Watching a slower, less polished version go out with your name on it triggers something deep. Pride. Fear. The nagging voice that says people will think you’ve lost your edge. Keep in mind here that I’m not advocating for you to submit sub-par work. Never do that. Just let go of your perfectionism and trust your students.

That discomfort is the price of multiplication.

Every time you feel the urge to take over, that’s your old identity fighting for survival. Every time you cringe at an 80% draft, that’s your ego protecting itself. Every time you think it would be faster to just do it myself, that’s the bottleneck pattern reasserting control.

The discomfort means you’re growing past your old ceiling.

If this transition felt easy, you wouldn’t be doing it right. The discomfort is evidence that you’re letting go, you’re changing, you’re actually becoming the leader your lab needs instead of the hero your ego wants to be.

The goal isn’t to eliminate the discomfort. The goal is to recognize it as a signal that you’re on the right path. Feel the cringe. Let the draft go anyway. Watch your student grow. Repeat until the new identity feels as natural as the old one.

Getting back your time in 60 days

Here’s what changes if you commit to this for 60 days.

Week 1 feels wrong. You’ll add a draft to your Feedback Queue and you will itch to open it. You’ll schedule a mentoring session and spend the whole time resisting the urge to grab the keyboard. You’ll watch a student struggle with something you could fix in two minutes. It will feel inefficient. It will feel slow. It will feel like you’re failing them.

Week 3, something is likely going to change. A student sends you a draft and it’s… better. Not because you fixed the last one. Because you discussed the principles with them instead. You notice you explained the same structural issue to two different students, so you write it down. Now it’s a document. Now it’s part of your new system.

Week 6, the compound returns start showing. A student catches their own contribution issues before you point it out. Another one brings a draft to your meeting and walks you through the structure before you even ask. The drafts aren’t perfect. But they’re diagnostic. You can see what they understand and what they don’t. You’re mentoring them like a good coach.

By day 60, you’ll notice something strange. You have more time. Because your team is carrying more of the load. The drafts still come. But now they come with fewer structural problems. The teaching sessions are shorter because the students are asking better questions. The queue moves faster because you’re quickly reviewing them.

Ten to 15 hours a week, back in your hands simply by changing what you do with the 30 minutes you spend on each draft.

Start with this one action

The next time a draft lands in your inbox, don’t open it.

Add it to a queue. Schedule a 30-minute teaching session within 48 hours. Show up to that session with one question: What principle, if taught now, would prevent this problem in their next draft?

That’s it. One draft. One trigger. One teaching moment.

If you do that once, you’ll see how it feels. If you do it for 60 days, you’ll see how it compounds.

The best professors are the ones who build the best writers, not the ones who write the best papers themselves.

Your best skill got you here. Now it’s time to build a better one.

Lennart

P.S.: Curious to explore how we can tackle your research struggles together? I've got three suggestions that could be a great fit: A seven-day email course that teaches you the basics of research methods. Or the recordings of our AI research tools webinar and PhD student fast track webinar.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How do I stop being a bottleneck PI in my lab?

A: Stop rewriting everything yourself and switch to a clear delegation and feedback system. Set expectations, use structured feedback, and require students to revise their own text so you coach instead of fix.

Q: How many hours can I save by delegating more effectively as a PI?

A: Many PIs can recover around 10-15 hours per week that they currently spend fixing student work. Over a semester, that equals several weeks of deep work time for grants and strategy.

Q: How do I train students to write papers without rewriting everything myself?

A: Share concrete examples, define what good looks like, and use a stable feedback template. Make students revise based on your comments and explain their changes, instead of replacing their text with yours.

Q: What is the best way to give feedback on a bad Discussion section?

A: Focus first on structure and argument, not line-level edits. Point out missing claims, weak links to results, and absent limitations, then model one strong paragraph and have the student rewrite the rest to match.

Q: How long does it take for a delegation system to pay off in a lab?

A: The first few weeks feel slower because you are coaching instead of fixing. With consistent use, many PIs see a clear drop in editing load and better student drafts within about 60 days.

Q: Is it fair to expect students to handle most of the writing?

A: Yes, because writing is a core research skill and part of their training. Your role is to provide standards, structure, and feedback so they can grow into independent authors, not to be their ghostwriter.

Q: When is it okay for a PI to fully rewrite a student’s draft?

A: Reserve full rewrites for true emergencies like immovable deadlines or serious student crises. Treat these as exceptions, then debrief afterward so they still learn from the changes.

The AI Research Stack Bonus

Paid subscribers get the complete lab delegation system: a printable PDF protocol to hand every team member, a 60-day bottleneck elimination system checklist that walks you from bottleneck to publishing machine, and 3 AI prompts that generate diagnostic questions to send, one that analyzes your editing patterns, and a script for running your first mentoring session. ↓