Key Points

- Trying to write, cite, argue, and edit all at once causes cognitive overload.

- Use atomic notes to capture one idea per note with clear links.

- Build a synthesis matrix to map arguments across sources and spot gaps.

- Write using the hourglass (PEEL) paragraph structure for flow and clarity.

- Follow a weekly staged system: notes, paragraph drafts, integration, polishing.

You’re drowning. In notes. In deadlines. In the crushing weight of your dissertation that refuses to write itself. Every morning to every night, you shuffle the same fragments, rearrange the same quotes, and still. Nothing.

Most PhD students try to transform their research notes into polished paragraphs in one heroic outing. The common mistake? Attempting to synthesize sources, assemble arguments, and perfect your prose all at the same time.

Such cognitive overload creates paralysis. Your brain maxes out trying to juggle five different writing tasks simultaneously. You stare at the screen for hours, producing nothing but frustration. It’s like Ferris Bueller took your paragraphs for a day off and forgot to return them. And all you do is attempting to blow into the empty NES cartridge that is your mind trying to find the words in there, but knowing they just won’t load.

Stop trying to do everything at once. I mean it.

The Writing Crisis Is Real

Research shows 80+% of graduate students struggle with procrastination, particularly when facing complex writing tasks.

Your brain betrays you, it often cannot juggle more than 7 chunks of information (chunking is grouping information into meaningful units) without dropping everything. Your working memory can only handle 4 ± 1 items of information at once (without chunking or rehearsal), but memory span varies based on factors like word length, familiarity, or speaking time. When you try to write, cite, argue, and edit simultaneously, you’re asking your brain to perform an impossible juggling act. The result? Most PhD students take three times longer to write than necessary, producing work that still needs extensive revision.

Break your writing into distinct cognitive layers. Here’s exactly how to do it.

How To Transform Notes Into Readable Paragraphs (to Finish That Thesis)

You’ll learn to separate the three core writing processes that your brain naturally wants to combine.

- First, create an atomic note system where each idea lives as its own complete unit with unique identifiers and explicit connections to related concepts.

- Second, build paragraph skeletons using the hourglass method: broad context narrowing to specific evidence, then expanding to implications.

- Third, layer in your intellectual voice through staged construction that respects your cognitive limits while maintaining academic rigour.

Here’s the system:

Step 1: Atomic Notes

Forget massive, undifferentiated text blocks. Each note should contain exactly one complete thought in your own words. Give it a descriptive title that captures the essence, something you’ll actually remember like “Why attention fractures under cognitive load.” Link it explicitly to related concepts. To build your cognitive architecture.

When you externalize your thinking into bite-sized units, you free your working memory to focus on writing rather than remembering.

In Obsidian: Create one note per concept with a descriptive title like “Working Memory, 7 item limit (Miller 1956).” Inside, write the core idea in one sentence. Then add your interpretation and link to related concepts using [[double brackets]]. When you search “working memory,” all related notes surface instantly.

In Notion: Build a searchable database. Each entry = one concept. Add properties that mirror how you think: Core Idea (one sentence), My Take (your interpretation), Source, and Related Concepts. Use filters to pull up everything about “cognitive load” when writing that section. The visual database lets you see patterns your linear notes hide.

In Apple Notes: Use the folder system as your categories (e.g., “Cognitive Psychology,” “Writing Process,” “Research Methods”). Title each note with the concept + context: “Working Memory: Why we can only handle 7 things at once.” Inside, keep it simple: one paragraph for the concept, one for your take, then use hashtags for connections (#cognitiveload #writingblocks #attention). Apple’s search finds everything instantly. Type “working memory” and every related note appears, including where you mentioned it in other notes. My favourite (and slightly) lazy method.

The key is to use descriptive titles you’ll actually remember. Not “Note-047” but “Why humans can’t multitask: Cognitive bottleneck theory.” When writing, you search by concept, not by code name.

Turn each source insight into a discrete intellectual unit. From foundational theories to cutting-edge findings, you’re gathering pre-digested ideas your brain can now actually manipulate. Basically, you’ve gone from Jon Snow knowing nothing to Bran Stark seeing everything.

Atomic Notes

- Each note = one complete idea, in your own words.

- Connect it to other concepts with links or hashtags.

- Give it a descriptive, memorable title.

Step 2: Thematic Synthesis Matrix

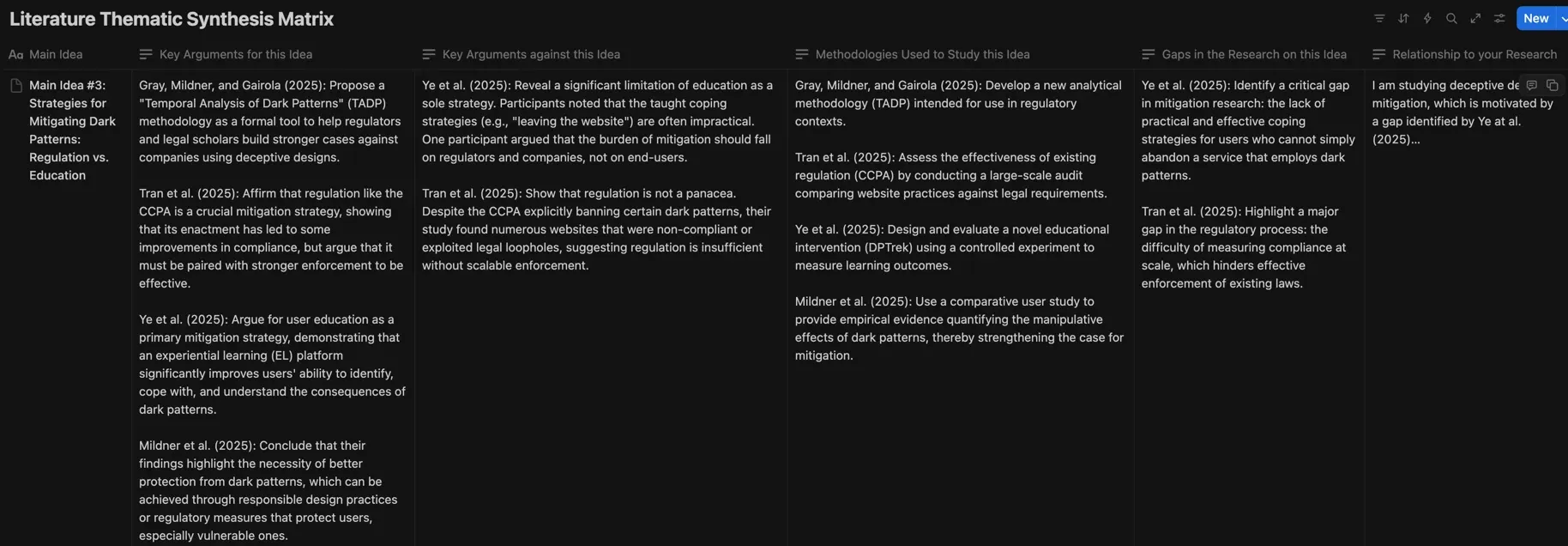

Create a grid. Rows represent your key arguments (but I also like to keep track more generally of main ideas). Columns represent your sources. Fill each cell with specific evidence that source provides for that argument. Empty cells reveal research gaps immediately. Dense cells show where your evidence is strongest.

I also have a version of this that presents columns as the key arguments for an idea and the key arguments against an idea. I also like to keep track of the methodologies used to study this idea. Then I usually have a column about the gaps in research related to this specific idea. And finally, I like to keep track about the relationship to my own research.

Such a visual mapping reduces the cognitive load of remembering what goes where. Your brain can focus on connections instead of recall.

| Argument/Theme | Smith (2023) | Jones (2024) | Brown (2022) | Research Gap | My Work |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Load Limits | ✔ evidence | ✔ counter | Missing longitudinal studies | Core framework |

Thematic Synthesis Matrix

Create a grid:

- Cells = specific evidence each source provides.

- Rows = key arguments or themes.

- Columns = sources.

Enhancements:

- Add a column for how this connects to your own work.

- Add “for” and “against” arguments.

- Track methodologies used.

- Note research gaps.

Step 3: Hourglass Paragraph Structure

Start broad with context. Narrow to specific evidence from multiple sources woven together. Then expand again to implications and connections. This hourglass maps perfectly onto PEEL structure. Your Point starts broad (context). Evidence narrows the focus (specific sources). Explanation weaves them together. Link expands outward (implications). Same cognitive architecture, different labels.

Short sentences anchor. Medium sentences develop as they proceed. Long sentences synthesize multiple sources into coherent arguments that advance your field. Vary the rhythm. Make it palatable. To the reader.

Each atomic note becomes one E in your PEEL. Pull three related notes, you have three pieces of Evidence ready to slot in. No more staring at blank pages wondering what comes next. Your paragraph builds itself.

This flow is your Millennium Falcon, jumping readers to light speed without shaking them apart. Each paragraph is a story episode: The setup is your “Previously on,” the middle drops the twist, the ending lands the cliffhanger.

It starts in the Shire, wanders through Mordor, and comes back carrying fire. It’s Mario grabbing the star: familiar, surprising, unstoppable.

Every section (and every paper) takes your reader on the full ride: From comfort zone, to revelation, to meaning that stretches far beyond your page.

Write one layer at a time. Separate them. Turn this overwhelming task into workable steps that respect how your brain actually works.

Why this works when everything else fails:

Paragraph Structure

Each paragraph follows a natural flow:

- Point (broad context)

- Evidence (specific sources woven together)

- Explanation (synthesis, analysis)

- Link (implications and outward connections)

Paragraph Writing Tips

- Short sentences for anchors.

- Medium sentences to develop ideas.

- Long sentences to synthesize multiple sources.

This rhythm keeps readers engaged.

Why You Should Use Staged Paragraph Construction

The human brain wasn’t designed for simultaneous complex processing.

Cognitive Load Theory supports that frontloading your organizational work dramatically improves writing quality. So, it’s generally a good idea to separate planning from drafting for better coherence. We have limited capacity for simultaneous control-dependent tasks, such as synthesizing sources, constructing grammatical sentences, and maintaining argumentative flow. In practice, this means once you’ve freed working memory from overload, you can reallocate it toward structure and clarity.

The real power? Your brain shifts from desperate juggling to deliberate architecture.

When you separate note-taking from synthesis, synthesis from drafting, and drafting from editing, each process gets your brain’s full attention. Arguments clarify. Evidence flows. Your academic voice can now emerge with fewer constraints.

Staged Weekly Writing System

- Monday: Note Day: Process research into atomic notes.

- Tue/Wed: Paragraph Days: Draft topic sentences, map evidence, then integrate.

- Thursday: Integration Day: Polish transitions using echo method.

- Friday: Polishing Day: Check citations, flow, and clarity.

Advanced Implementation Protocol

Here’s exactly how to implement this system this week.

Monday: Note Processing Day

Turn your weekly research into permanent atomic notes. Each insight gets its own note with a unique identifier. Connect related ideas explicitly. This is intellectual carpentry: Measure twice, cut once, and your argument won’t wobble as much.

Tuesday/Wednesday: Paragraph Construction Days

Never write the whole paragraph at once. First, draft just topic sentences (pick the strongest of three if you feel like rewriting) for your sections, bullet points. Then map your evidence visually before attempting integration. You can slot them in a sub bullet points. Only after evidence is laid out do you add some brief analytical reflection. Finally, write transitions. Or hey, just prompt any LLM to help you “segue from {current paragraph} into the next concept: {provide next topic sentence}”. Five paragraphs per day using this method beats twenty paragraphs of cognitive overload.

Thursday: Integration Day

Connect new paragraphs to existing structure. Refine transitions using the echo method: repeat key terms from topic sentences throughout, but with progressive development (could also put this in a prompt). You’ll be able to create both unity and momentum without clunky mechanical transition words.

Friday: Polishing Day

Now, and only now, do you polish. Check citation integration. Refine your academic voice. Make sure things are really clear. This is where AI tools can really help, but only for enhancement, never for complete generation. The brainwork is yours. The booster is in how it shows up on the page.

Quick Tip for Source Integration

Stop presenting sources sequentially like a grocery list. I like to call them dinner conversations (like imaging your sources are having a dinner conversation with one another).

Create intellectual conversations between researchers. “While Smith (2023) argues X, Jones (2024) extends this framework by suggesting Y, though both overlook the crucial factor of Z identified in earlier work by Brown (2022).”

You want to avoid a situation where you just list things off like: A said this, B said this, C said this. This is mechanical citation. But you don’t want that. You want dynamic academic dialogue. Your paragraph should turn into this moderated discussion where you’re the intellectual host guiding readers through competing perspectives toward your unique contribution.

The Weekly Writing System That Actually Works

Productive academics don’t write when inspired. They follow systems.

We know the usual patterns: 90 to 120 minute focused sessions during peak cognitive hours. Daily writing, even 30 minutes, beats marathon weekend sessions. But let it flow. If you go hard, go hard. If you go light, go light, but avoid not writing. Always be writing. Your consistency will compound. Small daily progress puts an end to the anxiety of looming deadlines.

But most importantly: Always respect your cognitive limits. When you feel overwhelmed, reduce scope. Focus on one intellectual connection per session. Use visual mapping (like concept maps) to offload memory burden. Never attempt full paragraph construction when cognitively depleted.

The academics who master these systematic approaches don’t just write better. They write with less suffering. They transform academia’s most dreaded task into manageable, even enjoyable, intellectual practice.

Writing isn’t thinking. Writing is the expression of thinking you’ve already done.

So stop trying to do both at once.

Build your atomic notes. Layer your paragraphs. Separate your processes. Respect how your brain actually works.

Start with one note. One complete thought. One descriptive title.

The rest follows.

FAQ

Q1: How do I know if my atomic notes are good enough?

If each note makes sense to you six months later without extra context, it’s good.

Q2: Can I use AI tools to build my synthesis matrix?

Yes, prompt an LLM to extract key arguments, but always verify accuracy. My prompt for paid subscribers is below.

Q3: How many sources should I integrate per paragraph?

At least 2-3, woven together into a conversation, not listed separately in the main body of sections that are not results.

Q4: What if I fall behind on the weekly system?

Scale down. One note per day is still progress. Consistency compounds.